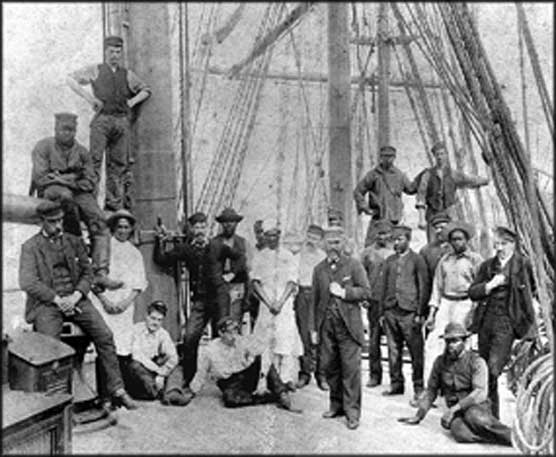

Seamen on the whaling bark Wanderer make ready to cast off for another voyage. The exact location is unknown, but probably New England.

Whaling: Opportunities for African Americans in a Hard Business

The whaling industry, centered until the 1870s in New Bedford, employed a large number of African Americans. This was in part due to the Quaker tradition of tolerance in the New Bedford area, but more importantly, to the large demand for manpower in an expanding industry requiring unusually large crews.

Some black seamen in the business were Americans, from the Northeast and the South, some were from the West Indies, and a significant group was from the Cape Verde Islands off the African coast. Whatever their origin, black seamen found acceptance as hard workers and skilled mariners in an industry that was physically demanding, dirty, and often financially unrewarding.

When the center of the industry moved to San Francisco in the 1870s, African Americans continued to form a large percentage of the crews. The whaling business was no doubt the largest employer of African Americans seamen on the West Coast until it ended shortly before World War I.

|

| NPS Captain William T. Shorey and family. |

William T. Shorey (1859-1919) was a famous captain in the last days of whaling. He was born in Barbados, the son of a Scottish sugar planter and an Indian creole woman. Shorey began seafaring as a teenager and in 1876 he made his first whaling voyage.

Whaling brought him to California and he married the daughter from a leading African American family in San Francisco. In 1886 he became the only black West Coast ship captain. Known for his skill and leadership, Shorey experienced many adventures and dangers at sea with multiracial crews before his retirement in 1908.

Over time, larger, steam-powered vessels took the place of obsolete sailing ships and black seamen were forced to accept inferior employment on ships as cooks and stewards. The era of significant participation by blacks in whaling ended in 1923 when the Wanderer went aground off Nantucket, MA.

Black Men in Foreign Flag Sailing Ships

The crew of the British ship Rathdown,

photographed in San Francisco in 1892.

The two men in aprons are the cook and

steward but the other black men are all seamen.

Black men were often found among the crews of British ships, and even some German and Scandinavian ships, calling at West Coast ports. Black faces appear in about one quarter of all the foreign flag crew photographs in the park's collections. In many cases the men are clearly cooks or stewards, but in a surprising number of photos the men are obviously seamen, living and working on terms of complete equality with other members of the crew. The majority of black seamen in British ships were probably from the West Indies, but we do not have references for African Americans hired as seamen in foreign ships at New York and other East Coast ports.

The Navy: A Mixed Legacy

Throughout most of its history, the Navy has followed a policy of employing African Americans in all enlisted grades. They were active in both naval and privateer crews during the Revolutionary War. A brief period of discrimination ended with the War of 1812. From then until 1915 African Americans served in the ranks of all naval vessels. During the Civil War, at least six African Americans were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. Only officer ranks were closed to them during this period.

In 1915 an executive order from President Wilson ordered segregation for all branches in the military. Until 1942 African Americans were recruited only as messmen. During the rest of World War II, opportunities for African Americans gradually expanded and the first twelve officers were commissioned in 1944. In 1946 a Navy order finally ended official segregation throughout the Navy.

Desegregation in practice took somewhat longer to achieve, but was finally accomplished, and today the Navy can once again take pride in its tradition of racial equality.

|

NPS Captain Michael Healy of the Revenue Cutter Bear. |

Captain Healy, an African American, rose to the rank of Captain in 1883. From 1886 until 1895 Healy commanded the Bear, a steam barkentine, on patrols in the North Pacific, Bering Sea, and Arctic Ocean. The Bear was virtually the only law in these Northern regions, enforcing quotas in the sealing industry, protecting native people from exploitation, and keeping the peace among white settlers. She performed many feats of heroic rescue among the whaling fleet and the isolated outposts of trappers and hunters.

Captain Healy was known as a stern disciplinarian, and was accused of brutalizing his seamen on at least one occasion. Although formally exonerated from these charges, it is no doubt true that he was a hard man, performing a difficult and demanding duty.

This information thanks to the National Parks Service (NPS)