Printed on: Thursday, May 6, 2010

Fall 2001, Vol. 33, No. 3

Black Men in Navy Blue During the Civil War

By Joseph P. Reidy

|

|

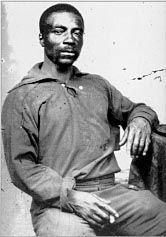

Civil War sailor George Commodore. (NARA, Records of the Veterans Administration, RG 15)

|

Given the wealth of available information about Civil War soldiers, the comparative poverty of such knowledge about Civil War sailors borders on the astonishing. Two explanations account for this imbalance. First, the broad narrative of presidential leadership and the clash of armies in Virginia that Ken Burns's The Civil War told so powerfully all but excludes naval forces from the tale. Second, existing accounts of the naval Civil War have focused on the strategic role of naval forces in the contest, the governmental architects of naval policy, the naval officers who masterminded operations, and the innovations in technology and weaponry to the near exclusion of the enlisted sailors' war. No image of "Jack Tar" comparable to Bell I. Wiley's classic portraits of "Billy Yank" and "Johnny Reb" fills the popular imagination or the works of Civil War historians.1

Because the navy, unlike the army, was racially integrated, understanding the history of black sailors requires some effort but even more interpretive caution to unravel it from that of all Civil War sailors. Exploring the similarities and differences in the experiences of black and white enlisted men must avoid viewing the racial groups in strictly monolithic terms that do not allow for internal complexity and diversity and shifting, if not altogether porous, borders. The work must also beware currently popular understandings of the black soldiers' experience. Often framed around the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, that tale depicts stoic sacrifice and daunting perseverance in pursuit of freedom and equality that in the end was crowned with "Glory," the impression conveyed by the popular feature film. The black sailors' story fits awkwardly, if at all, within that image.

The study of African Americans in the Civil War navy must begin with determining their numbers. During the first decade of the twentieth century, when the secretary of the navy was quizzed about the service of black men in the Civil War, senior officers who had served in the conflict recalled that approximately one-quarter of the enlisted force was black. In a grand display of false precision, the secretary's office concluded that 29,511 black men had served by taking the known figure of Civil War enlistments (118,044) and dividing by four.2 That figure remained essentially unchallenged until 1973, when David L. Valuska's dissertation revised it downward to slightly less than ten thousand men, based upon his survey of surviving enlistment records.3 Over the past decade, a research partnership among Howard University, the Department of the Navy, and the National Park Service has made possible an examination of a fuller array of records than earlier researchers, working as individuals, were able to explore.4 As a result, nearly eighteen thousand men of African descent (and eleven women) who served in the U.S. Navy during the Civil War have been identified by name.5 At 20 percent of the navy's total enlisted force, black sailors constituted a significant segment of naval manpower and nearly double the proportion of black soldiers who served in the U.S. Army during the Civil War.6

At the start of the conflict, the army and the navy drew upon separate traditions regarding the service of persons of African descent. Following adoption of the federal Militia Act in 1792, the army excluded black men, and the prohibition remained in effect until the second summer of the Civil War. The navy, in contrast, never barred black men from serving, although from the 1840s onward regulations limited their numbers to 5 percent of the enlisted force. When the war began, several hundred black men were in the naval service, a small fraction of those with prewar experience and a figure well below the prescribed maximum. During the first ninety days after Fort Sumter, when nearly three hundred black recruits enlisted, fifty-nine (20 percent) were veterans with an average of five years of prior naval service per man.7 Over succeeding months, the proportion of black men in the service increased rapidly. At the end of 1861, they made up roughly 6 percent of the crews of vessels. By the summer of 1862, the figure had climbed to nearly 15 percent.8

At first, navy officials did not treat black manpower separately from their general need for men as the service expanded and as volunteer army units competed for the able-bodied. With enlistment centers at the major Atlantic ports from Chesapeake Bay through New England, recruiters could draw upon the international seafaring fraternity to supplement the recruits from the seaboard states. By the end of the war, some 7,700 of the roughly 17,000 men whose place of nativity is recorded had been born in states that remained within the Union. Not surprisingly, the coastal states contributed the largest numbers of men: New York and Pennsylvania roughly 1,200 each, and Massachusetts and New Jersey more than 400 each. Many of these men had been mariners before the war, and still others had worked on the docks and shipping-related businesses of the seaport cities. Additional recruits with prior maritime experience on the lakes and rivers of the nation's interior also enlisted; these included 420 natives of Kentucky. The largest number of black men from any of the northern states— more than 2,300 in all— hailed from Maryland. The maritime culture of Chesapeake Bay, with its numerous tributaries and the port of Baltimore, offer part of the explanation for the large number of Marylanders in naval service. The size of the Maryland contingent also benefited from a spring 1864 agreement between army and navy officials to transfer nearly eight hundred black Marylanders from incomplete units of the U.S. Colored Troops into the navy.9

Another fifteen hundred men were born outside of the United States, chiefly Canada and the islands of the Caribbean.10 Like their counterparts from the United States, the foreign-born men entered service for a variety of reasons. John Robert Bond, for instance, a mariner of mixed African and Irish descent from Liverpool, England, enlisted during 1863 "to help free the slaves," as his descendants recall. Seriously wounded the following year, he was discharged and pensioned after a long recuperation. He settled in Hyde Park, Massachusetts, amid other black Civil War veterans.11

The remainder of the 17,000 men whose place of nativity is recorded— some 7,800 in all— were born in the seceded Confederate states. The firsthand experience that these men had with slavery distinguished them from their freeborn northern counterparts. Moreover, whereas northern freemen could enlist when they chose, men held in bondage often had to rely on the circumstances of war for the opportunity to do so. Not simply awaiting their fate, black men escaping from slavery helped create opportunities for the federal government to protect them and accept their offers of service. By September 1861, the volume of requests from commanders of naval vessels regarding authorization to enlist fugitive slaves reached such proportions that Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, a Connecticut native of antislavery bent, felt obliged to act. Welles permitted the enlistment of former slaves whose "services can be useful," stipulating that the "contrabands" be classified as "Boys," the lowest rung on the rating and pay scales and one traditionally reserved for young men under the age of eighteen.12 (The term "contraband" itself had within weeks of Fort Sumter sprung into widespread use throughout the North as a rationale for treating such persons as plunder under international conventions of warfare.) The practical effect of this policy became evident when Flag Officer Samuel F. Du Pont established federal control of the harbor at Port Royal, South Carolina, in November 1861. This beachhead eventually became the home port of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, with repair and supply facilities that employed nearly a thousand contrabands. At the same time, vessels in all the squadrons began taking fugitive slaves on board, enlisting the men as needed and forwarding others to places of safety.13

The large concentrations of enslaved African Americans on the plantations along the Mississippi River and the strategic importance of the river to both sides assured that Secretary Welles's directive regarding the employment of contrabands would have special relevance to the Mississippi Squadron. In April 1863, as the combined army and navy assault on Vicksburg, Mississippi, took shape, Flag Officer David D. Porter instructed the commanders of vessels to take full advantage of "acclimated" black manpower.14 Under these guidelines, more than two thousand men enlisted on the vessels that plied the Mississippi and its tributaries.15 The refugee camps that sprang up in Union-occupied areas also proved a rich source of recruits. In the camps of coastal North Carolina, for instance, recruiters from the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron displayed posters promising good pay and other amenities and urging volunteers to "Come forward and serve your Country."16

The success of these efforts to recruit black men from the Union-occupied regions of the South tipped the demographic balance among black sailors. Largely free men with considerable naval experience at the start of the war, over time the force included growing numbers of recently enslaved men with only limited maritime experience. Not surprisingly, most were from the states where Union naval forces operated: the Carolinas, Mississippi, and Louisiana. The largest contingent of southern-born men, however, was the Virginians, more than twenty-eight hundred strong, numbers of whom had been sold before the war from their native state to plantation regions farther south. The fact that nearly six thousand (roughly 35 percent) of the black sailors whose nativity is known came from the Chesapeake Bay region is striking. Even more so is that more than eleven thousand men were born in the slave states as against four thousand born in the free states. Even allowing for the fact that a small fraction of those from the slave states had been born free, nearly three men born into slavery served for every man born free. Hardly predictable from the record of black sailors in the antebellum navy, this demographic division profoundly influenced the black naval experience during the war.

Quarterly muster rolls of vessels clearly demonstrate the navy's reliance on black manpower between 1862 and 1864, as the following table indicates.17

Table 1: Aggregate Percentages of Black Enlisted Men Serving on Board U.S. Naval Vessels by Quarter of the Calendar Year, 1862 - 1865

| |

Quarter

|

Percentage

|

1st Quarter 1862

|

8

|

2nd Quarter 1862 through 2nd Quarter 1863

|

15

|

3rd Quarter 1863 through 3rd Quarter 1864

|

23

|

4th Quarter 1864 through 3rd Quarter 1865

|

17

|

4th Quarter 1865

|

15

|

Source: Muster Rolls of Vessels, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, Record Group (RG) 24, National Archives.

| |

From the spring of 1861 through the fall of 1864, the percentage of black men increased steadily from a starting point of less than 5 percent to a peak of 23 percent. In this context, the Navy Department's rule-of-thumb estimate from early in the twentieth century that one quarter of the enlisted force was black comes very close to describing the reality from summer 1863 through summer 1864. By the fall of 1865, after most wartime volunteers had been discharged, black men still constituted 15 percent of the enlisted force, more than three times the percentage of black men in service at the start of the war.

The racial demographics of the enlisted force varied— often significantly— by squadron and by vessel. In the European Squadron, for instance, a handful of ships cruising the North Atlantic in pursuit of Confederate commerce raiders and blockade runners, the number of black sailors was small. Given that most of the ships were outfitted and manned early in the war, the demographic profile of Kearsarge, perhaps the most famous of the bunch, wherein black men made up 5 to 10 percent of the crew, was entirely typical. In the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, which drew men from the traditional enlistment points along the northeast Atlantic seaboard as well as from the coastal regions of Virginia and North Carolina, the proportion of black enlisted men was considerably higher than that of the European Squadron. The Mississippi Squadron, which drew recruits from Cincinnati, Ohio, and Cairo, Illinois, as well as from its areas of operations along the Mississippi River and its tributaries, relied most on black manpower. In David Farragut's West Gulf Blockading Squadron, the proportion of black sailors fell well short of that in the Mississippi Squadron or the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron.

Table 2: Percentages of Black Enlisted Men Serving on Board U.S Naval Vessels in Three Representative Squadrons, Second Quarter of 1864

| ||

Squadron

|

Percentage

| |

North Atlantic

|

25

| |

West Gulf

|

20

| |

Mississippi

|

34

| |

Source: Muster Rolls of Vessels, RG 24, National Archives.

| ||

At the level of individual vessels, the racial demographics of crews reflected a more complex array of variables, including the type of vessel, its tactical mission within a larger unit of operations, and the personality of the captain, his officers, and the ship's company. The broader cultural biases that associated persons of African descent with menial labor and personal service also influenced these demographic patterns. The disproportionate presence of black sailors on supply ships illustrates this point. During 1863 and 1864, virtually every man attached to USS Vermont, moored at Port Royal and serving as the supply ship for the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, was black.18 At Hampton Roads, where another vintage ship-of-the-line, USS Brandywine, stored supplies for the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, the proportion of black enlisted men ranged between 47 and 57 percent during 1863 and 1864.19

In analogous fashion, black men filled an inordinately large number of the enlisted billets on the barks and schooners that served as colliers and ordnance storeships. Between 67 and 100 percent of the enlisted men serving in Charles Phelps, Fearnot, J. C. Kuhn, Albemarle, Arletta, and Ben Morgan were black.20 In the supply steamers New National (Mississippi Squadron), William Badger (North Atlantic Blockading Squadron), and Donegal (South Atlantic Blockading Squadron), the proportion of black enlisted men ranged from 63 to 100 percent.21 Conversely, black men made up the smallest proportion of men in the sloops of war and other ocean-going warships that were the backbone of the late antebellum navy and the workhorses of the blockading squadrons.

The black enlistees who had been slaves— in many instances down to the time of enlistment— stood apart from the freemen of all colors and nations. Often accepted into service on a supposition of inferiority, stigmatized as "contrabands," and rated and paid at the lowest levels of the rating and pay scales, these men often could not escape the stereotypes cast upon them no matter how creditably they performed their assigned duties. In, but not necessarily of, the crews with which they served, the contrabands performed the manual labor necessary to keep a steam vessel functioning and the busywork that officers considered the foundation of good order and discipline on warships: holystoning, scrubbing, scraping, painting, and polishing. Although black men routinely served on gun crews at general quarters, they stood a far greater chance of serving with small-arms crews, armed with swords, rifles, and pistols, for repelling boarders, and with damage control units, armed with water hoses for dousing fires and battle-axes for cutting away damaged spars and rigging. Small-arms crews consisting of contrabands generally exercised separately from those consisting of white sailors.22

USS Miami (Courtesy, Naval Historical Center)

|

USS Hunchback (NARA, NWDNS-111-B-2011)

|

Given the pervasive prejudice among white officers and enlisted men, black men sought out their own company as much as possible. Such a pattern of association derived largely from the rating structure, but enlistment patterns and prewar associations also played a part. A surviving photograph of USS Miami illustrates. Around the time of the photograph, about one-quarter of the approximately one hundred enlisted men were of African descent, nearly all contrabands rated as boys and recently enlisted at Plymouth, North Carolina; a number shared the surnames of Etheridge, Johnson, White, and Wilson.23 In a similar photograph of Hunchback, the cluster of black men to the right invites similar scrutiny. During the middle of 1864, approximately twenty-five of the roughly one hundred enlisted men were of African descent. Fifteen of the men were contrabands from Maryland who had recently been transferred from the army to the navy.24

Joseph P. Reidy has taught U.S. history at Howard University since 1984 and for the past three years has also served as the Associate Dean of the Graduate School. He has published widely on slavery, the Civil War, and slave emancipation in both scholarly and popular journals. At present he directs the African-American Sailors Project at Howard University, from which work the present article derives.

Articles published in Prologue do not necessarily represent the views of NARA or of any other agency of the United States Government.

|

The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

8601 Adelphi Road, College Park, MD 20740-6001 •

Telephone: 1-86-NARA-NARA or 1-866-272-6272

Also see Turn of the century black sailors.

Also see African American Crew on WWII Destroyer Escort.

Telephone: 1-86-NARA-NARA or 1-866-272-6272

Also see Turn of the century black sailors.

Also see African American Crew on WWII Destroyer Escort.